Jason Little is the first to receive an implant to test the breakthrough technology along with a neural-enabled prosthetic hand, which reconnects feeling in his missing hand to his brain, allowing him to feel sensations in his amputated hand. During the clinical trial, Little was able to regain feeling when using a specialized prosthetic arm and hand with sensors, permitting him to accomplish everyday tasks once again.

On May 27, 2011, Little lost control of his Toyota 4Runner while driving on an interstate in Florida during a rainstorm – ultimately resulting in the loss of his left hand and part of his arm below the elbow. Now, ten years later, he recently completed a trial for the first prosthetic that restores feeling in missing limbs via an implanted neurostimulator in his upper arm, which has vastly improved his quality of life and even allowed him to feel the sensation of holding his wife’s hand in his prosthetic for the first time in years.

In 2017, researchers at Florida International University’s (FIU) Department of Biomedical Engineering, led by Dr. Ranu Jung, reached out to Little to see if he would be interested in being the first to participate in the recently approved government-funded trial of this new technology. Since he was accustomed to regularly wearing a prosthetic, had a higher level of amputation, and was not born with a limb deficiency, Little seemed to be the perfect fit.

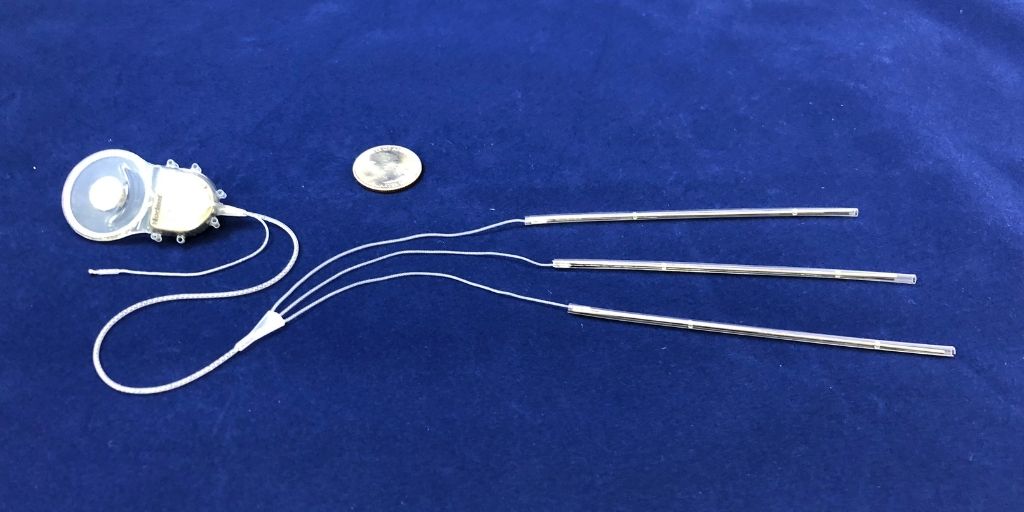

By the time the trial began, he had already undergone four separate surgeries, three of which were at the time of amputation. After considering the risks associated with undergoing yet another, he agreed to participate. On March 19, 2018, he underwent a 12-hour operation to have the specially engineered neurostimulator implanted in his upper arm that would send signals up the nerves that once connected his hand to his brain.

During the two-year trial, Little tirelessly traveled between his home in Orlando to the lab at FIU’s College of Engineering in Miami for testing, where researchers connected him to a computer and sent signals to the implant, as he provided verbal feedback on the location and intensity of the sensations he was experiencing. Through this exercise, researchers mapped the nerves in his upper arm to areas of a hand that no longer existed, which unintentionally reduced the phantom pain he was experiencing – a phenomenon that was not expected but gladly welcomed.

Now, thanks to the implant, he can decipher these signals in real-time and identify the size or hardness of objects without any other feedback. For example, if his hand is fully open, the sensor sends more stimulation versus when the hand is closed. A pressure sensor in the thumbs sends feedback on the strength of his grip. This helps him maintain a firm grasp so he doesn’t drop things, as he did previously using a prosthetic without sensory assistance. Little describes the signals he receives from the system as a tingling, vibrating, electrical pulse in his phantom hand.

“I can’t thank Dr. Jung and her team enough for allowing me to participate in this study. Being the first at anything can present its own set of challenges but, this prosthetic allows me to accomplish simple tasks that most non-disabled people take for granted every day. Since I now get feedback about the grip I have on something, I can cut a tomato without crushing it, unscrew a water bottle cap without spilling water and, most importantly, feel what it’s like to hold my wife’s hand again,” said Little. “There were times I didn’t know if it would be worth the travel time or the hours spent in the lab. However, I stuck with it and saw the two-year study through to the end. Now, I hope to educate and inspire others to be vulnerable enough to put themselves in less-than-comfortable situations. The courage to do that might one day positively impact their lives or the lives of those around them. Although this technology is still in its infancy, there is a real opportunity to improve the quality of life for thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands of people around the world with different ailments or disabilities. It’s a legacy I am very proud to be a part of.”

Following the success of Little’s first in-human trial, researchers are now developing a new state-of-the-art prosthetic hand with more sensors, one in each digit and another in the palm, providing an opportunity to stimulate more nerves and, potentially, create a more lifelike sensation for amputees like Little. Additionally, researchers in other fields have begun looking into using this neurostimulation technology to develop other applications such as a signal-based insulin-releasing pump for diabetics and a device that could alert people with quadriplegia when they need to relieve themselves so they can live without the burden of catheters.